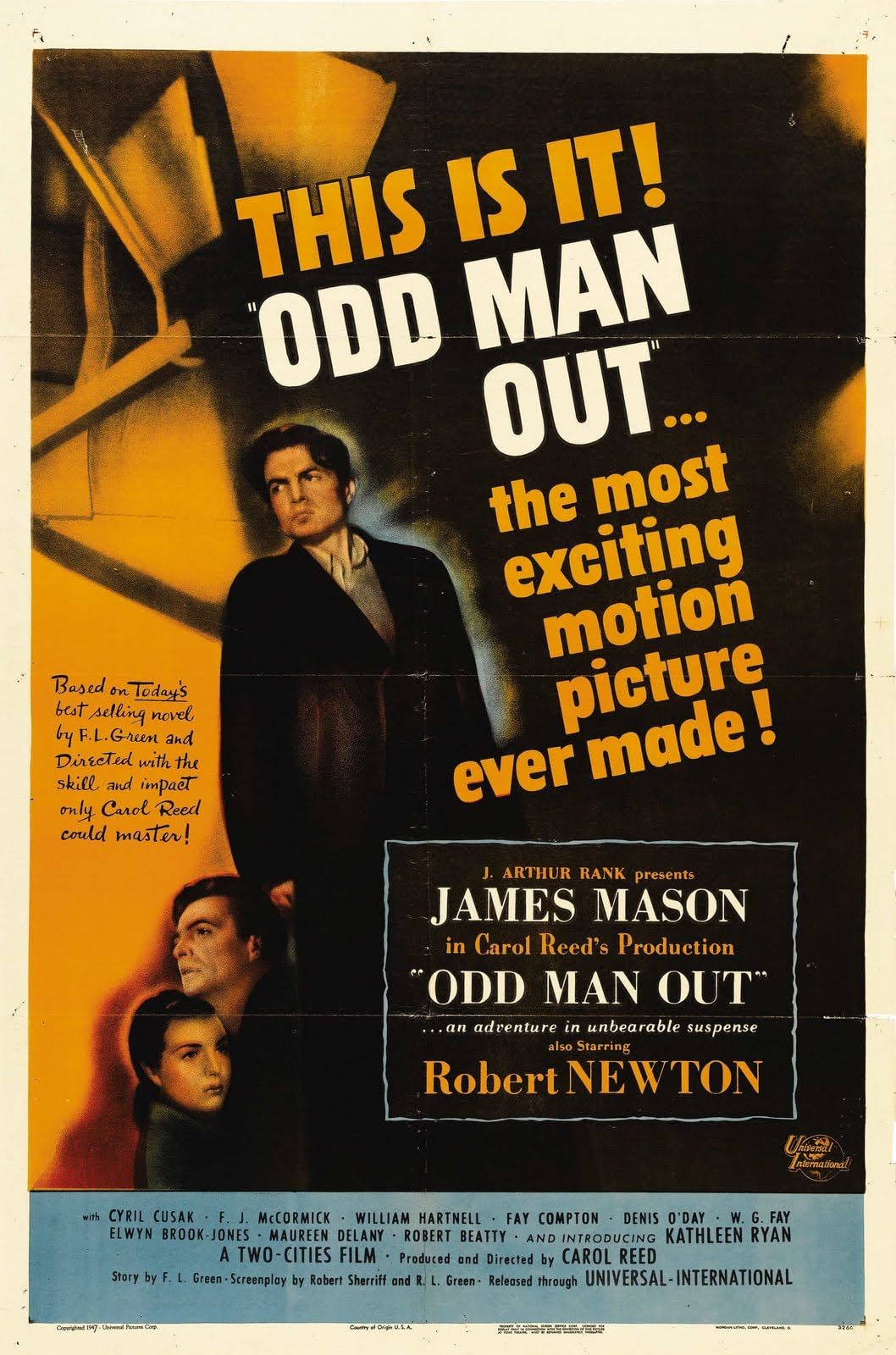

Sometimes people suggest that The Third Man which was directed by Carol Reed and stars Orson Welles in a pivotal role was also secretly directed by Welles. Or that at the very least Welles gave Reed plenty of advice. The Third Man indeed contains the types of skewed camera angles and shrewd use of shadows and light that Welles so loved, but anyone suggesting that Carol Reed was incapable of such things has apparently never watched Odd Man Out. For it contains many such moments and it came out three years before The Third Man.

Odd Man Out stars James Mason as Johnny McQueen, an Irish Nationalist leader who becomes wounded after a botched robbery attempt. The film follows along as his friend and the police scour the city looking for him, while continually checking back on him as he hides out in an air raid shelter, a local pub, and finally an artist’s residence.

What is remarkable about the film (besides the filmmaking itself which is brilliant) is how much the film makes us care about all of these characters. Johnny is a criminal. He commits that robbery for the money, not out of desperation or need (there are political motivations, but the film never delves into what they are). He kills a man while fleeing the crime scene. While the film shows him remorseful for that act it never once lets us forget it. But it also makes us feel and care for him as a person.

Thematically the film delves deep into that question as to how we are as a society to deal with and react to a criminal – a fugitive from justice.

A couple of elderly women see Johnny fallen on the street. They think he has been hit by a truck. They take him in and attempt to patch him up. But once they realize he has been shot, and thus who he is, they change. They are no longer helping a wounded man but are aiding and abetting a criminal.

A priest asks for information about Jonny’s whereabouts. He won’t protect him from the police but would like to hear his confession. A local street hood tries to sell his hiding place to the highest bidder. An artist wants to paint him as he dies. Johnny’s girl Kathleen (Kathleen Ryan) will do anything to save him, even risk her life.

The film takes us through all of these interactions with great care and style. It doesn’t so much judge these characters as it asks us to ponder their dilemmas. Shot in stark black and white it makes great use of its sets, its location settings, shadows, and lights. It is breathtaking to look at. It is the sort of film that makes you think maybe Orson Welles learned a thing or two from Carol Reed.

It made for the perfect conclusion to Noirvember.