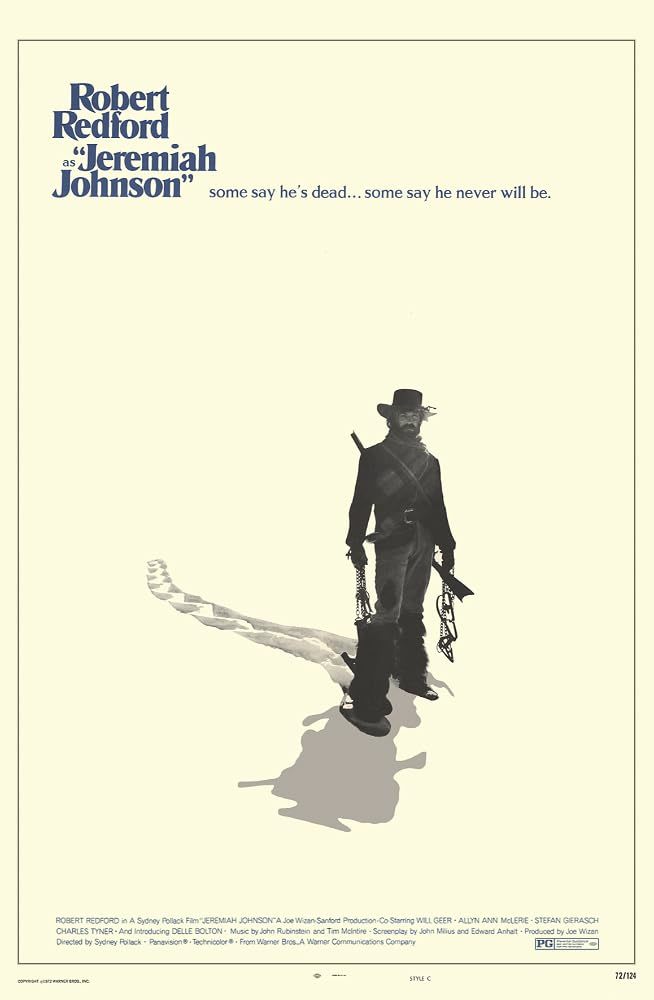

Jeremiah Johnson was a real mountain man who, as legend has it, killed, scalped, and ate the livers of some 300 Crow Indians. From what I’ve read he seems like a pretty rough-and-tumble guy. Director Sydney Pollack teamed up with Robert Redford and turned him into some kind of folk hero in their film based upon the legend.

Redford plays Johnson as a man who initially heads to the mountains to get away from society and truly become something, some kind of man. He isn’t naive or untrained like Chris McCandless from Into the Wild. He has some skills hunting and surviving in the wild. Just getting to the Rockies in the late 1800s was an adventure in itself.

But life in the mountains is different than life in the plains. Johnson find himself in trouble. He struggles making fire in the cold, wind, and snow. He can’t catch a fish in the mountain streams. He has better luck with wild game, but not much.

Cold and nearly starved, he stumbles across an old grisly bear hunter named Bear Claw (Will Greer). The old man teaches him how to survive in the mountains. He becomes good at it. He thrives. He learns the ways of the various Indian tribes in the area, but doesn’t befriend them. He’s a man who likes to be alone.

In time he comes across a cabin that has been attacked by Indians. A child was killed, and the husband is missing. A young boy has survived and his mother who has gone crazy from the ordeal. Johnson begins caring for the boy. Later Johnson makes a mistake in a trade with a Flathead tribe and finds himself with a wife.

This man of solitude now finds himself with a family. It is hard on him at first, especially since he does not speak his Crow wife’s language and the boy is mute, but he learns to love them and they make a life together.

Then tragedy hits and Johnson becomes the liver-eating man of legend.

Pollack and cinematographer Duke Callaghan film it like poetry. Pollack calls it his silent picture and there are long scenes in which not a word is spoken. Shot in and around the Rocky Mountains in Utah it is often stunningly beautiful. Redford does some of his best work. All of this is periodically puncturated by songs from Tim McIntire and John Rubinstein. They are sung in the Appalachian folk tradition and are a little too on the nose declaring the themes of the film. Also they are just bad.

It is interesting that they turned this story of a rugged mountain man, known for his ruthless slaying of countless natives into the story of a good man who just wants to be left alone, at peace in nature. He rarely takes action himself, the mountains or outsiders force him into it. Even in the end when he becomes the Crow Slayer, it is always them who attack him. It does feel like they are turning into a folk hero. I doubt that is where the truth really lies. But we’ll never really know the truth anyway, as the true story was turned into legend long ago and the facts have long since been lost.

Not that it matters. True or not the film is quite good, longing and beautiful. A tale of a time long past, but of mountains that still amaze with their grandeur.