Apologies for not getting a Friday Night Horror movie up this week. I had planned to make this film that post as it blends both elements of film noir and horror, but Friday turned into a very long day. Work was a series of mistakes and irritations and then my daughter performed at the high school football game. I was happy to support her but by the time we got home, I was nothing but exhausted. I did manage to watch this, but there was no chance my brain could come up with something to write about it.

Four days later and here I am.

I think The Night of the Hunter was the very first film noir I ever watched. I can’t be quite sure of that because I didn’t always know what film noir even was so it is possible something else was seen earlier than this, but I don’t know what that would be. I don’t even know exactly when I first watched this film. I remember being spellbound by it, but nothing surrounds that memory to give me a clue as to what time frame it occurred. At a guess, I would say college or maybe just after.

It doesn’t really matter, but I like tracking these things. It was definitely early days in my life as a cinephile. I had started watching classic movies and understanding them as art, but not so early that watching a film like this was a revelation.

I hadn’t watched this in years and maybe it is a revelation. It’s just so damn good. So strange in some ways, and beautiful. It was the first and only film ever directed by actor Charles Laughton. It bombed at the box office and they never gave him another chance in the director’s chair. I weep at what we missed because of that.

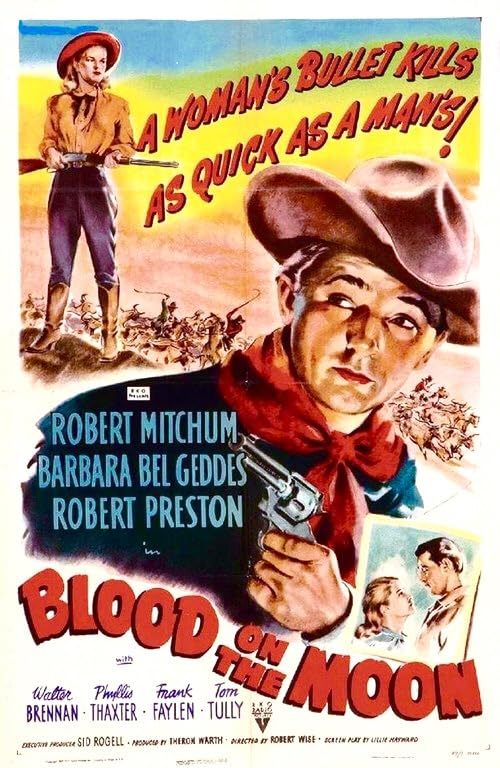

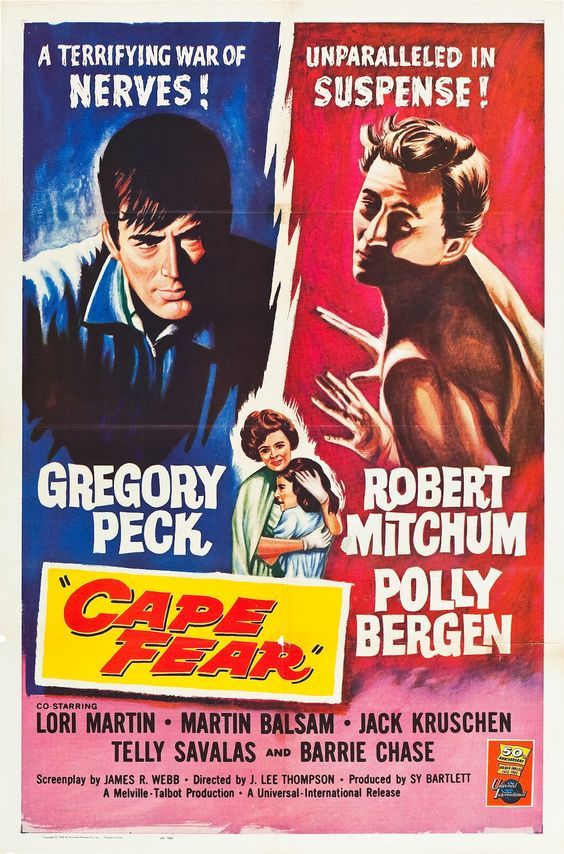

Robert Mitchum plays Harry Powell a man who uses the veil of religion to lure women into his snare, marry them, kill them, then leave with their money. He’s got Hate tattooed on one hand and Love on the other. He loves to tell a flamboyant story about how Love conquers Hate which generally enthralls the listener.

While in prison for theft he meets Ben Harper (Peter Graves) a man sentenced to be hanged. In his sleep, Ben mumbles something about the $10,000 he stole and something else about his kids knowing where the money is hidden.

That’s all Harry needs to go on the prowl again. Once he’s out he finds Ben’s wife Willa (Shelley Winters) and quickly seduces her. Well, maybe seduce isn’t the right word. He woos her, talks her into marriage and then basically casts her aside. There is one chilling scene, their wedding night, where she comes in ready for the lovemaking and he lectures her that sex is but for childbearing, and since she’s already got two there is no need for them to consummate their marriage.

The kind veneer disappears for the children as well quite quick. At first, he acts as a loving father and gently works for them to spill the secret of the money, but wen that doesn’t work he gets angry and mean. The girl, Pearl (Sally Jane Bruce) dotes on Harry, but the boy, John (Billy Chapin) knows what’s up.

Soon enough the kids are on a skiff floating down the river, desperately trying to escape the murderous grip of Harry. They wind up at the home of Rachel Cooper (Lillian Gish) a widow who lost her own child to the Depression and has started taking in homeless children. There they find kindness, grace, and love.

But while the story is really good, the filmmaking makes this a true classic. It is very theatrical in its production. The sets look stagey. Even the supposed outdoor scenes have an artificiality to them. It is designed to constantly remind you that what you are watching isn’t real, it is a story. A morality play. But it is also gorgeously put together.

There is a scene that takes place in Harry and Willa’s bedroom. It is a strangely shaped room with a sharply angled ceiling and a high window. Light shines brightly through that window but shadows loom. The camera sits way back, through what would have to be a wall. blackness frames the room, again as if we were watching a play.

Another scene is shot inside a screened-in porch at Rachel Cooper’s house. She sits in a rocking chair with a shotgun in her lap. Outside stands Harry Powell, waiting. The light inside the porch is off. We see her in shadow. A streetlight illuminates the preacher. Then a young girl enters with a candle. Now we see Rachael more clearly but it darkens our view of Harry Powell. The candle is blown out and he’s gone. It is masterfully staged.

Everything about the film is masterful. Robert Mitchum has never been more menacing. Shelley Winters never more vulnerable. And Lillian Gish is an angel.

It is a great movie. A great film noir. One of the very best.