Between 1934 and 1943, James M. Cain wrote The Postman Always Rings Twice, Mildred Pierce, and Double Indemnity, three stone-cold classics. These made him one of the godfathers of the hard-boiled detective stories. They made three great movies off of those novels, which also makes him the godfather of film noir.

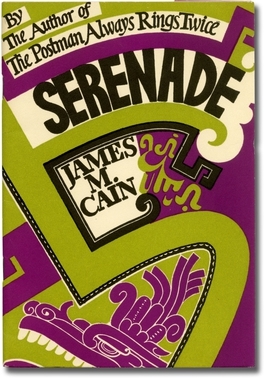

He wrote several other books during this time. I’ve only read one of them, Serenade, and didn’t particularly care for it, but those big three are amazing. He wrote many more books after this period, too, and I only just realized he kept writing up until his death in 1977. In fact, he was writing The Cocktail Waitress when he died.

I say writing it, but in fact he had mostly finished it. Or rather, he had finished it a few different times. Originally written in the third person, Cain became unsatisfied with this and rewrote it in the first person, changing the vernacular to fit his protagonist’s voice. He then sent a draft to his publisher, who demanded he change the ending. A final draft was never sent, and so the novel was shelved after Cain died.

Many years later, the good people at Hard Case Crime publishing went digging for it and found several different drafts. They had to make some decisions on which parts of which drafts to use, but ultimately published what they consider the final book in 2012. But this isn’t a case where they hired some new writer to complete an unfinished novel; they simply had to decide which parts of various finished drafts to edit into what we now have on our shelves.

The end result is pretty good. Like I said, I haven’t read any of the books Cain wrote after Double Indemnity in 1943, but my understanding is that his later books tackled other interests besides crime. The Cocktail Waitress was then an attempt to return to form, perhaps to stir up commercial interest that had waned.

Our narrator is Joan Medford, and her story begins with her husband’s end. He was a deadbeat and a drunk who used to beat her. He died in an automobile accident, leaving her with a young son, a house, and a pile of unpaid bills. The accident was a little suspicious, but the cops couldn’t find enough evidence to book her for it, so they let her be.

Because she’s telling her story (into a tape recorder to get her side of every crime – there will be several – onto an official record), we’re never quite sure if what she’s telling is the truth. She is absolutely an unreliable narrator.

Because of the unpaid bills, she takes a job as a cocktail waitress. It’s one of those joints where she has to wear a skimpy outfit and accept the fact that her customers are going to hit on her, pinch her posterior, and sometimes ask for more.

She’ll meet two men at this job that will change her life. The first is Earl White, an elderly, very wealthy gentleman with a heart condition that makes it impossible for him to have sex with Joan or anyone else. This doesn’t keep him from making passes at her, but he tips extremely well, so she encourages him. So much that he eventually asks her to marry him. He promises he’ll behave, and anyway, if he doesn’t, he’ll literally die from trying, so what has she got to lose?

That would certainly get her out of all her financial troubles, set her up for life, and allow her son to live a good life. Currently the boy is living with his dead husband’s sister, a woman Joan hates. She suspects the woman wants to keep her boy permanently, but she knows she’s got to get something more financially permanent in her life in order to take him back, and Earl would be just the thing.

The other man is Tom. He’s young, fiery, and handsome. Also broke. Also a bit of pig. The first time he meets him, he’s drunk as hell, and he slides his hands right up her skimpy waitress outfit and into places no man should go without asking first. She gives him her what-for for doing that, but it kind of turned her on. Or something. She’ll eventually let him take her out. For her trouble, he takes her to a place with curtains around the booths so that couples can do things people really shouldn’t do on a table where others might want to eat. She kind of likes it this time, but then remembers her deal with Earl and splits before things get too heavy.

And that’s the crux of the story. Earl will give her all the stability she craves, but she’s not attracted to him. Also, he just can’t help himself. Whether it will kill him or not, he’d really like to get it on with Joan. Then there is Tom, who cannot help her financial situation out, and he’s kind of lecherous, but damn it if he doesn’t turn her on.

If you know anything about James M. Cain, you’ll know this story will have some deadly twists. I won’t spoil them, but let’s just say the law gets back on her trail, and it will be difficult for her to get out of it this time.

Cain’s stories were always a little bit sleazy. He liked writing about characters on the rough side of the tracks and never strayed away from sex in his stories. Lust is all over The Postman Rings Twice and Double Indemnity. He goes pretty hard in that direction in this story. I know it was written in the 1970s when those boundaries had been pushed farther by others at this point, but it did feel wild to read him going as far as he does in this story.

It also feels like an older man trying to keep up. Or a once great writer trying to relive his glory days. And you can definitely feel some of the editing going on. I don’t ‘know that I could point you to a specific page where you can tell that the editor used an older draft or whatever, but overall it did feel a little disjointed. But also, I rather enjoyed reading it.

I remember reading Mildred Pierce for the first time and stopping after several pages, my heart racing and a smile on my face. I immediately told my wife she had to read it. I wanted to shout it to everyone that this was an amazing book. It was just that good. I did not have a moment like that while reading The Cocktail Waitress. But that doesn’t mean I’m unhappy I read the book either. I’m glad I did. I’d recommend it to anyone interested in Cain’s novels. I’m so glad they were able to put it together and give it to the world.