Editors Note: The first couple of paragraphs of this post talk about a counter that I no longer have installed on the site. I’m keeping them up because some comments refer to it, and ultimately I want to keep almost everything I’ve written on this site to stay up as a sort-of historical marker to my thoughts.

Made a few changes to the site. Added a permanent link in the sidebar to a posting about the books I have read since coming to France. For the last several years I have meant to start keeping track of the books I read in a given year, but never do a good job of it. I believe this blog will help me do the trick. If I get real good I might actually review/rate them as I go along. If people seem to like it I just might add movies and music to the list as well.

My counter (which is now set to produce random numbers on the actual blog site, but give me real numbers by logging in) from bravenet.com has some sort of referral program with it. It says it is supposed to bring a lot of new hits to my site. It is pretty vague about how it does it and I’m thinking it probably has to do with pop-up ads. Since my IP address is disallowed from the program I’m gonna need some help. If you are getting pop-ups when you go to my blog please let me know. If that is the method of getting more hits, I’d rather find a better way. Pop ups stink!

Anyway to get along with the subject of this blog. I have been trying to read some of the classics of the mystery genre. Or more literally the detective subgenre of the mystery genre. The three main writers I have been reading in this subgenre are Raymond Chandler, Dashiell Hammett, and Agatha Christie. All three are very good writers in their own right, but whom bring something different to the genre.

I first started reading Dashiell Hammett because I had heard more about him through the film The Maltese Falcon (1941 )and he was purportedly a big influence on the Coen Brothers. I have read all of his novels: The Maltese Falcon, Red Harvest, The Glass Key, The Dain Curse, and the The Thin Man. Each one is original and very different stylistically. It’s as if he intentionally wrote each novel as a different sub-sub genre. Red Harvest uses the unnamed Continental Op (who was the main character in many of his short stories as well as The Dain Curse) as a prototypical hard-boiled private-eye to tell his story. This character uses allegiances in two rival gangs to clean up a small city while trying not to go “blood simple” (excited to the point of amorality by excessive violence). The Coen Brothers were highly influenced by this book using blood simple as the title of their first movie, and many of it’s plot points in their gangster movie, Miller’s Crossing (1990). It also influenced other films such as Akira Kurasawa’s Yojimbo (1961), Sergio Leone’s A Fistful of Dollars (1964), and many more.

Hammett’s The Dain Curse again uses the Continental Op as his story teller but this time he is entwined in an episodic, melodramatic mystery. Its plot is as convoluted as it gets involving stolen jewels, drugs, a religious cult, and murder to name a few things. It’s also my least favorite of Hammett’s novels.

In The Maltese Falcon, Hammett turns things right again. Though everyone remembers Sam Spade as being portrayed by Humphrey Bogart in the 1941 John Huston picture. There were actually two other movies based on the novel (1931’s Dangerous Female and 1936’s Satan Met a Lady) that were lackluster at the box office. Bogarts portrayal of the hardboiled, but sensitive at heart private eye made him a star. That picture is pretty much spot on with the novel. Both are considered classics of the genre. The subgenre for Hammett here is the quest story with a wild assortment of characters. Sam Spade is our detective hero sorting through classic oddballs to find the mysterious, and very valuable bird of the title. For beginners into Hammett’s writings (or for detective stories in general) this is an excellent place to begin.

The Glass Key is a political drama without much of a detective in sight. Oh, it’s still dark and cynical as all get out, but it deals more with the corruption of city officials than any murder mystery. It also was a great influence on Miller’s Crossing and was made into a very good film noir of the same name in 1942.

The Thin Man is a more comic tale than any of his other work. Detectives are back this time in the guise of socialite Nick Charles and his wife Nora. Here Hammett plays up the high society couple as snoopers subgenre. When the Charles aren’t tossing back martinis and hob-nobbing with the rich they are solving murders. Hollywood came calling again with this one and created a whole series of Thin Man pictures starring William Powell and Myrna Loy.

***

Agatha Christie is probably the most well-known of the classic mystery writers. She wrote some 60 stories in her lifetime, most of which starred the eccentric, genius Belgian detective Hercule Poirot (Yes, I am now fully aware Christie wrote many books with other detectives including Miss Marple – Mat). I have only begun reading her novels having just finished Murder on the Orient Express and Death on the Nile. These novels are excellent representations of the “whodunit” version of the detective crime novel.

She masterly develops setting, imaginative characters and then deals in a murder or three. Clues are paced throughout in what has become a cliched manner. Though Christie has been imitated by umpteenth followers, nobody has topped her style. I typically do not enjoy mysteries because they follow a pattern Christie seems to have invented. The genre has gone stagnant with so many plots following the same pattern.

Odd-ball characters gather in a stylish setting. A murder is committed and then the reader is led down a path (often the wrong one) following a series of clues leading to the final scene where everyone is brought together and the mystery is explained. Christie follows this almost to a tea in both the Orient Express and Murder on the Nile. Yet, somehow she makes it all seem fresh. Her characters are inventive and thoroughly interesting. Hercule Poirot is the perfect detective. Smart, sensitive, and eccentric. And the following of clues is never too clever or too dull to drive me crazy. There are films based on both the books I’ve mentioned here as well as many of her other novels.

****

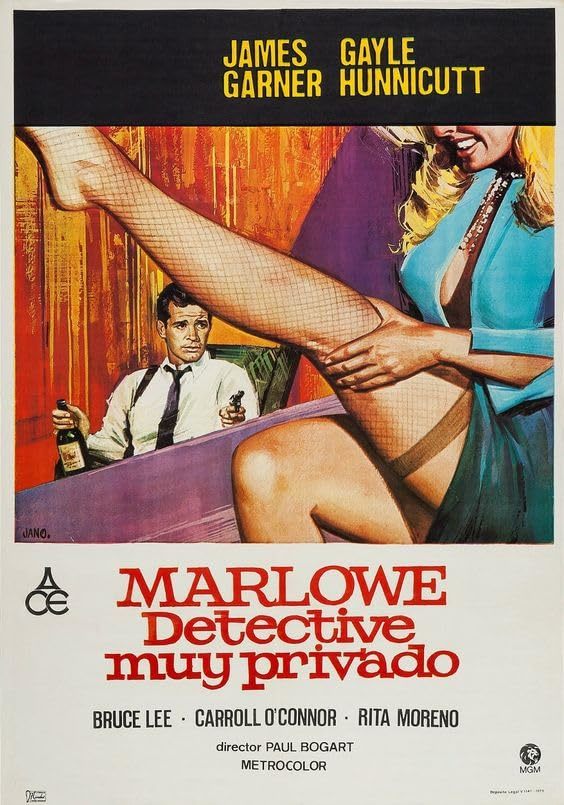

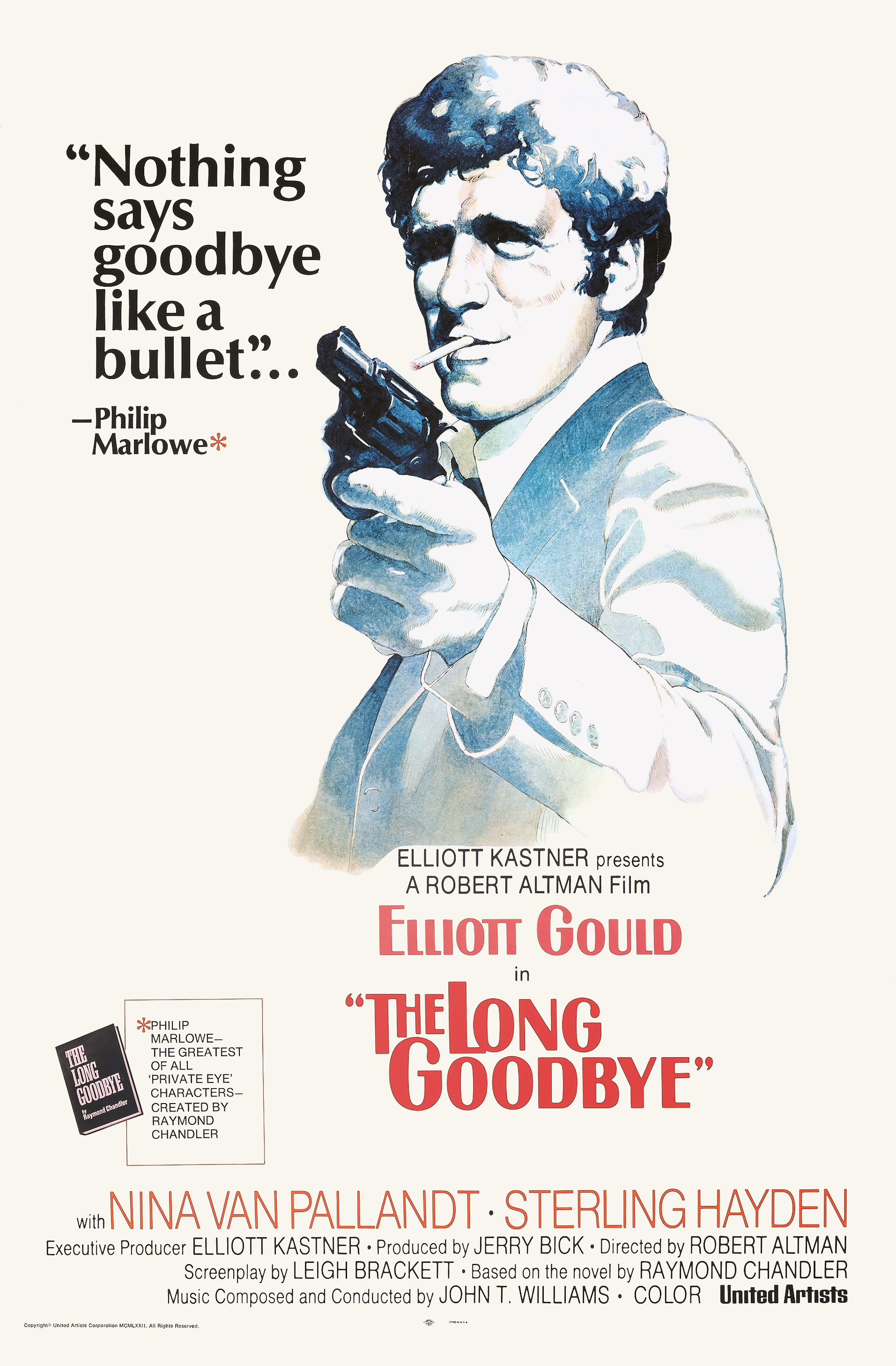

Raymond Chandler deserves a genre of his own. All of his novels feature the same main character, Phillip Marlowe. Marlowe is as hardboiled as they come. Dark, cynical, sarcastic, tough, and funny in a sick sort of way. There is almost always a murder (sometimes several), and plenty of drinking, smoking, and sometimes sex. Yet his stories are not so much about solving a crime as it is an insight into a certain time, in a certain place with certain characters. He dwells in the seedier, darker places of the American cities, and the human soul. His stories are never pretty, but often beautiful. I would hold up any of his novels high in the canon of literature.

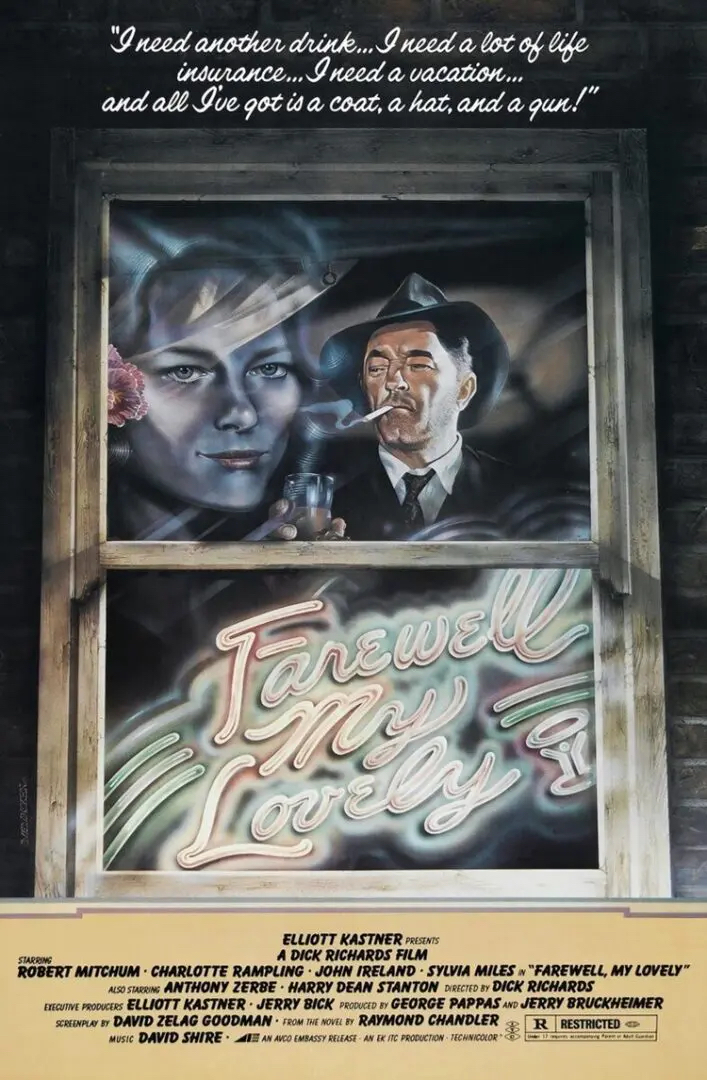

My favorite novel of Chandler’s that I have read was also made into an excellent Humphrey Bogart picture, The Big Sleep. Other novels of his that I have read include The High Window, The Lady in the Lake, and Farewell, My Lovely. All of them are well excellent and an excellent introduction into the detective mystery genre.

“”Tall, aren’t you?” she said.

“I didn’t mean to be.”

Her eyes rounded. She was puzzled. She was thinking. I could see, even on that short acquaintance, that thinking was always going to be a bother to her.”

—The Big Sleep (Chapter 1)

“I’m an occasional drinker, the kind of guy who goes out for a beer and wakes up in Singapore with a full beard.”

–The King in Yellow

Anybody who can write dialogue like that is well worth a read in my book.