Welcome back to Westerns in March. This is my fourth year doing this theme, and I’ve come to really enjoy it. There is something wonderful about this genre with its wide-open spaces, its barroom brawls, and its shootouts. So let’s get started.

Director John Sturges made Gunfight at the OK Corral in 1957 with Burt Lancaster as Wyatt Earp and Kirk Douglas as Doc Holliday. It is a darn good film. It ends with the titular gunfight.

Ten years later Sturges revisited the story with this film, a sort of sequel with James Garner in the Earp role and Jason Robards as Holiday. It begins with the gunfight at the OK Corral and then deals with its aftermath.

An opening title notes that “This picture is based on Fact. This is the way it happened” and Sturges did strive for more historical accuracy than is usually told with these stories, though, of course, he still changed quite a bit to suit his needs.

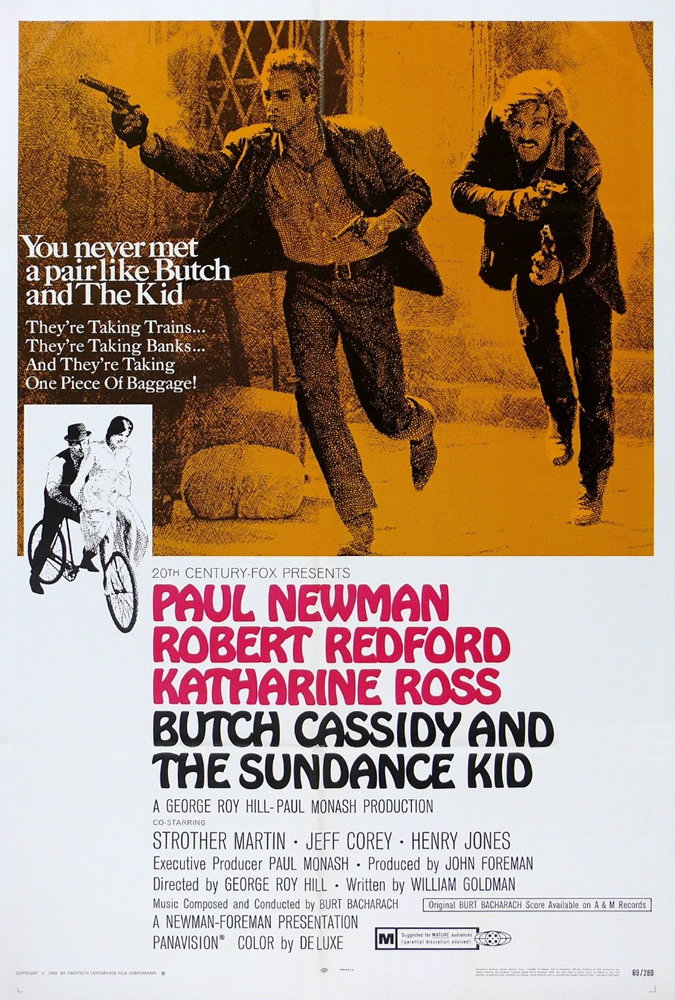

Ike Clanton (Robert Ryan) survived the gunfight (something he did in real life but did not in the previous film) and is now taking our heroes to court. He claims his men were unarmed and had raised their hands in the air when Earp and his men shot them dead.

Clanton loses the court case but sets up his own personal war with Earp, his brothers, and Holiday. Some of them get shot, some of them get killed. Wyatt is determined to stop them, but his moral code demands he do it legally. But his stubbornness makes him bend the law to suit his needs.

Robards is terrific as Doc Holiday. This is a very different performance from Val Kilmer’s portrayal in Tombstone, but it’s still real good. I never really buy James Garner as Wyatt Earp. I’m so used to him playing rascally wiseacres that it is difficult to buy him as the deadly serious man he’s playing here.

Robert Ryan barely has any screen time, and when he does, he isn’t nearly menacing enough. He’s the main villain, and he’s far too tame to be threatening. Which is a weird thing to say about Robert Ryan, who is usually so good at playing scary dudes.

Sturges’s direction is steady but not memorable. Ultimately, the film is worth watching for Robards’s performance and if you are interested in what happened after the famous gunfight.